When Christopher Columbus set foot on the Caribbean gem of Hispaniola back in 1492, it wasn’t just an exploration. It was the dawn of an era marked by turbulence, colonizing ambitions, and great upheaval.

In the hundred years that followed, the Taino people who were once the heartbeat of this island, found their civilization falling into oblivion, virtually erased from their ancestral homeland.

In its place rose the Spanish colonial capital Santo Domingo, an emblem of foreign conquest and cruelty.

Yet Hispaniola also quickly transitioned from a source of riches to a neglected backwater as its gold ran out and the colonists moved on to plunder new lands.

The island’s rapid cycles of prosperity and decline provided an ominous harbinger of what was to come across Spain’s rapidly expanding American empire.

The “Discovery” of Hispaniola

On December 5, 1492, after over two months at sea, the vessels of Christopher Columbus made landfall on the north coast of the island that would come to be known as Hispaniola.

Columbus was greeted by the Taino people, a native civilization of likely Arawak descent who inhabited the island they called Quisqueya (“Mother of all Lands”) and the broader Caribbean.

Mistakenly believing he had reached the East Indies, Columbus renamed the island “Hispaniola” and claimed it for Spain. He established a small fort near modern-day Cap-Haïtien which he left in command of 39 men.

The Taino People of Hispaniola

The Tainos on Hispaniola were not isolated savages as the Spanish often portrayed them. They possessed a complex society with practiced agricultural techniques, class divisions, and religious beliefs centered around zemi spirits.

Taino society was led by male caciques who inherited their status and controlled regional chiefdoms. Some women like Anacaona also held influential roles as spiritual, political, and military leaders.

Estimates suggest the Taino population on Hispaniola numbered between 300,000 and 1 million people when Columbus arrived. They spoke an Arawakan language and created artworks like zemi carvings.

The Tainos were initially hospitable to the Spanish, providing them with food and gifts. But the conquistadors soon took advantage of them through forced labor and appropriation of their lands and resources.

Early Spanish Atrocities and Taino Resistance

The Spanish settlers who remained on Hispaniola quickly commenced abusing, exploiting, and terrorizing the Tainos in their quest for gold and riches.

Led by the vicious governor Nicolas de Ovando, they tortured and killed Tainos for not meeting gold mining quotas. They raped Taino women and branded them with hot irons as punishment.

Some Tainos resisted the Spanish onslaught. The Taino cacique Enriquillo led a rebellion in the Bahoruco mountains which lasted over a decade, earning him the nickname “first rebel of the Americas.”

But most Spanish weaponry and technology proved superior, allowing for devastating casualties. Within two years of Columbus’s arrival, it’s estimated over half of the Tainos had died from violence, starvation, and European diseases.

The Rise of Santo Domingo

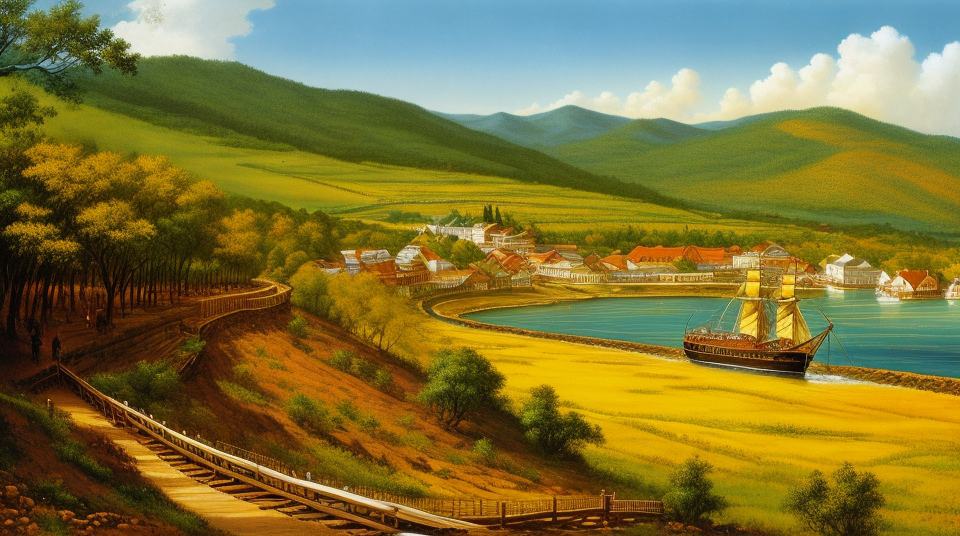

In 1502 Spain appointed Nicolas de Ovando as the new governor of the colony with instructions to bring order. He founded the capital Santo Domingo on the southeastern coast in 1502.

Serving as the first permanent European settlement in the Americas, Santo Domingo became the political, military, and religious center of Spain’s expanding colonies. Its fortified settlement was designed to intimidate the remaining Tainos.

Santo Domingo was built on the Taino chiefdom of the Higüey coastline. Ovando cunningly defeated the last Taino stronghold in the Xaragua region west of the Ozama River through trickery and betrayal. He executed the Taino queen Anacaona for leading a rebellion.

As the Spanish expanded their settlements, they decimated Taino populations through forced mining work, appropriation of crops, introduced diseases, and outright slaughter of those who resisted.

The Arrival of African Slavery

With the Taino population rapidly declining from brutal exploitation as well as foreign diseases, a new source of labor was needed on the island.

The Spanish started importing enslaved Africans in 1502, first only a few, then hundreds later that decade to toil on the colonists’ growing sugar plantations and in the gold mines.

Las Casas, though arguing for Taino rights, disturbingly advocated increasing Spanish exploitation of Africans taken by force from their homelands. The transatlantic slave trade only expanded in the following centuries.

African slaves on Hispaniola soon staged revolts of their own, launching a rebellion in 1522 on the plantation of Columbus’s son Diego. But their resistance was also eventually crushed by the better-armed Europeans.

Las Casas: Defender and Destroyer of Natives

Among early Spanish colonists, the most well-known advocate for indigenous rights was Bartolomé de Las Casas. After arriving on Hispaniola in 1502, the Spanish priest was appalled by the horrors inflicted upon the Tainos.

For the next 50 years until his death in 1566, Las Casas passionately defended the humanity of native peoples. His writings provide one of the most scathing indictments of Spanish cruelties in the Americas.

However, Las Casas’ compassion for the declining Taino population led him to recommend importing African slaves instead to replace their labor controversially. This likely contributed to the expansion of the transatlantic slave trade.

And while arguing for Tainos to be exempt from slavery, Las Casas was willing to accommodate some forms of forced or unpaid indigenous labor. His righteous advocacy had blind spots.

The Gold Rush and Hispaniola’s Prosperity

In the early 1500s, Hispaniola became a launching point for Spanish exploration of the Americas. Seeking rumored empires rich in gold and treasures, conquistadors invaded Cuba, Mexico, and Central and South America.

Hispaniola itself experienced a gold rush from mines in Cibao in the island’s north-central region. The uptick in gold mining and trade with Spanish colonies brought the island economic prosperity.

Sugar plantations also expanded, with production stimulated by the introduction of African slave labor. Hispaniola became Spain’s most profitable New World possession starting in 1516 under Charles V. For a time, the colony thrived from mining and agriculture.

The influx of Spain’s colonial riches soon made Seville one of the largest cities in Europe. But the prosperity was built on the deprivation and deaths of thousands of Taino and African lives through disease, forced labor, and violence.

The Decline of Hispaniola

By the 1530s, Hispaniola had begun a rapid decline. The primary cause was that its gold deposits had been mostly depleted, drying up the quick riches Spanish settlers craved.

But the Spanish colonists also proved unwilling to build lasting settlements or engage in the steady agricultural work needed to cultivate the colony as their own needs were met.

Instead, they rushed off to chase golden fantasies in Mexico starting in 1519, Peru in 1532, and later more South American colonies where Indigenous empires and complex societies provided new bodies to enslave and riches to plunder.

With Spanish colonists constantly leaving, Hispaniola’s population dwindled. Other than a small number of African slaves, Santo Domingo and the plantations were largely abandoned. A once-prosperous island now lay largely neglected.

Legacy of Decline and Oppression

Hispaniola’s swift transition from riches to decline provided an ominous sign of what was to come across Spain’s expanding dominion in the Americas.

The Taino civilization was essentially wiped out, with an estimated 96% perishing over the first 40 years. Tens of thousands more Africans would be enslaved on the island by the mid-1500s.

Santo Domingo’s brief opulence gave way to crumbling infrastructure. Hispaniola became a poor, neglected outpost as colonists rushed to pillage new lands. But the island’s tragic history was merely Spain’s first act of destruction in the Americas.

The conquest of Hispaniola inaugurated a pattern of indigenous peoples exploited and destroyed, of brief prosperity for colonizers built on slavery, and decline once resources were depleted. A cycle inflicted by European empires across the Americas for centuries to come.